This essay was written as a student project for HIST 7250: Practicum on the Place-Based Museum at Northeastern University in Fall 2024.

The Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770, which happened just outside this building, is one of the most well-known events in American history and is often seen as one of the key events that led to the American Revolution. However, many people cannot tell you exactly how many people died in the Boston Massacre or who they were. Let’s take a deeper look at the victims of the Massacre themselves in order to see them as real people and not just abstract figures.

Three of the five Boston Massacre victims died immediately. The first was Crispus Attucks. Attucks was of African and Indigenous descent and was an escaped slave from Framingham, Massachusetts. After he escaped his enslavement, Attucks began working as a sailor, and, at the time of the Massacre, he was living in the Bahamas. He was in Boston working on a ship headed to North Carolina. He was in the front of the crowd during the Massacre, and when the soldiers fired into the crowd, two musket balls hit him in the chest, killing him instantly. Attucks has been discussed throughout the centuries following the Massacre as the first victim of the Revolution, and since the mid-nineteenth century, his mixed race ancestry has been used to show how people of African descent have been an integral part of America’s history since the beginning.

The second immediate victim was Samuel Gray. Gray was a Boston resident and rope worker. He worked at Gray’s Ropeworks, a ropemaking factory that was located in modern day Post Office Square. He also had a reputation for being a notorious brawler who had been involved in a fistfight with British soldiers just days before the Massacre. Some sources even claim that Gray was the first man who was shot, but most historians agree that Attucks was the first death.

The third immediate victim was James Caldwell. Like Attucks, Caldwell did not live in Boston at the time of the Massacre. Instead, he was working on a ship called the Hawk that was docked in Boston before heading to the West Indies. Caldwell was only seventeen years old when two musket balls hit him in the back, killing him almost instantly. Since he was not from Boston and had no family in the city, his body was placed at Faneuil Hall until it was buried at Granary Burial Ground.

The Next Morning

On the morning of March 6, 1770, the fourth victim of the Boston Massacre perished from his wounds. This man was Samuel Maverick, a seventeen-year-old apprentice living in the North End. Maverick’s mother was widowed, so he became an apprentice to Isaac Greenwood and, as part of his apprenticeship, lived with Greenwood and his family. On the night of the Massacre, Maverick was eating dinner with some friends when he heard bells ringing. Assuming there was a fire in the city, he ran to the heart of the city: the Old State House. He saw the commotion in the street, and when the shots broke out, a musket ball hit him in the stomach.

Nine Days Later

The final official victim of the Boston Massacre was Patrick Carr. Carr had moved to Boston from Ireland in order to find a better life. Although Boston is famous today for its Irish heritage, at this time Irish people in the colonies were very prejudiced against, largely since many of them were Catholic. He also heard the bells ringing in the city and went to investigate with a friend of his and was hit by a musket ball in the stomach while crossing the street. Unfortunately common for the time period, it took many days for Carr to die of these wounds, and there was no way to spare his life. What’s interesting about Carr’s death is that since he was alive for over a week and lucid, he was able to give his testimony about what happened, unlike the other victims. What is even more interesting is that Carr said that the blame did not lay on the soldiers or the colonists. He said that since the guards were vastly outnumbered and being hit with rocks and other items, they could have fired much sooner but chose not to. To the dismay of the Sons of Liberty, Carr claimed that the famous Massacre was more of an unfortunate accident and tragedy.

Men and Martyrs

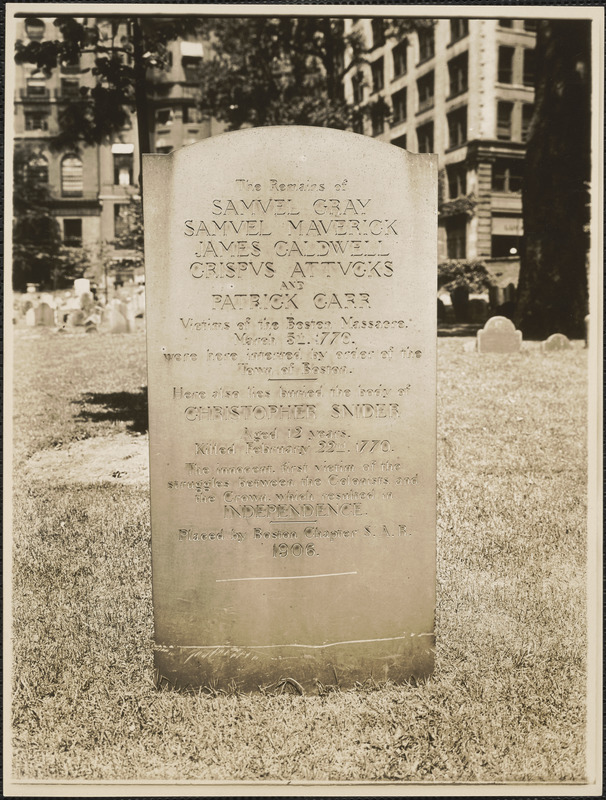

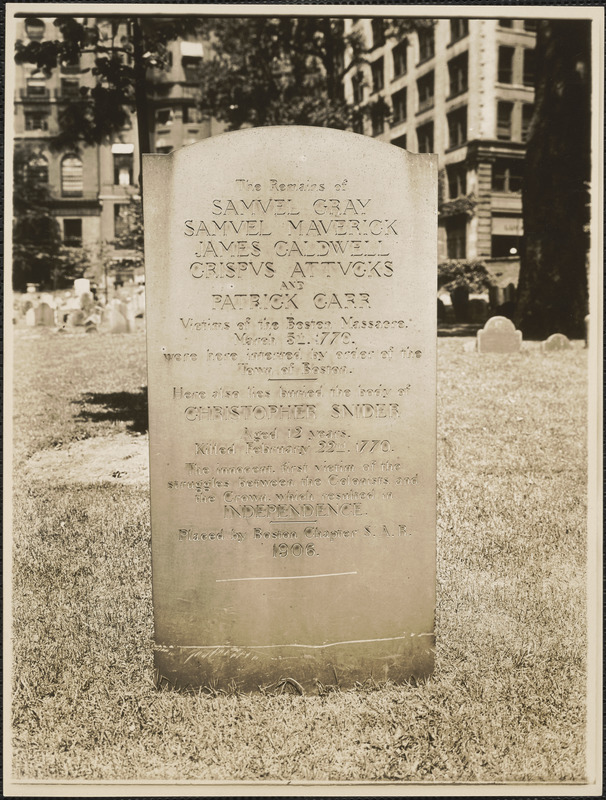

Despite the household name of the Boston Massacre, few people can tell you the names of the men killed, despite there only being five of them. Since it happened, the Massacre, and by extension the victims, has been heavily politicized and twisted into propaganda. The victims have become martyrs, and in many cases, their unique identities have vanished. They have stopped being Crispus, Samuel, Patrick, James, and Samuel and have instead become “the victims.” They even share a single headstone in Granary Burial Ground instead of individual ones. It’s important for us to remember that historical figures like these were people above all other things, no different from you and me. It’s important to keep this humanity in history, otherwise, the victims stop being people altogether.

This is a mid-nineteenth century depiction of the Massacre. It is more accurate than the famous Paul Revere painting.

A nineteen-twenties photograph of the victims’ shared tombstone.

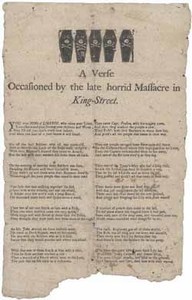

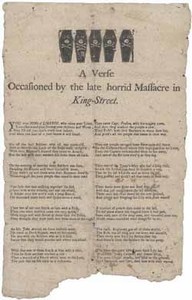

A poem written to commemorate the Massacre the same year it happened. Each of the coffins have the initials of the vicitms on them, and the victims’ names are said in the last stanza.

All information for this essay comes from Revolutionary Spaces, the National Park Services, and the Boston Massacre Historical Society.

Towards Beacon Hill

Towards Beacon Hill