This essay was written as a student project for HIST 7250: Practicum on the Place-Based Museum at Northeastern University in Fall 2024.

For centuries, Long Wharf has been a symbol of the flow of movement in the city of Boston, from colonial-era British troops landing and leaving to its modern function as a ferry hub. But Long Wharf was also a stagnant location for those sent to the Immigration Station and Detention Center until 1920.

Immigration Process

Immigrants on a ship in Boston Harbor, ca. 1895.

Boston did not have a single hub for processing immigrants like Ellis Island in New York or Angel Island in San Francisco in the early twentieth century. Instead, passengers disembarking from transatlantic voyages would have their documentation processed at small immigration checkpoints at the docks of each ocean liner company, primarily in Charlestown and East Boston. If there was trouble at these stations, a Board of Special Inquiry would be immediately convened to process special cases. If a person was still determined to be inadmissible, they would be sent to the Immigration Station and Detention Center at the end of Long Wharf.

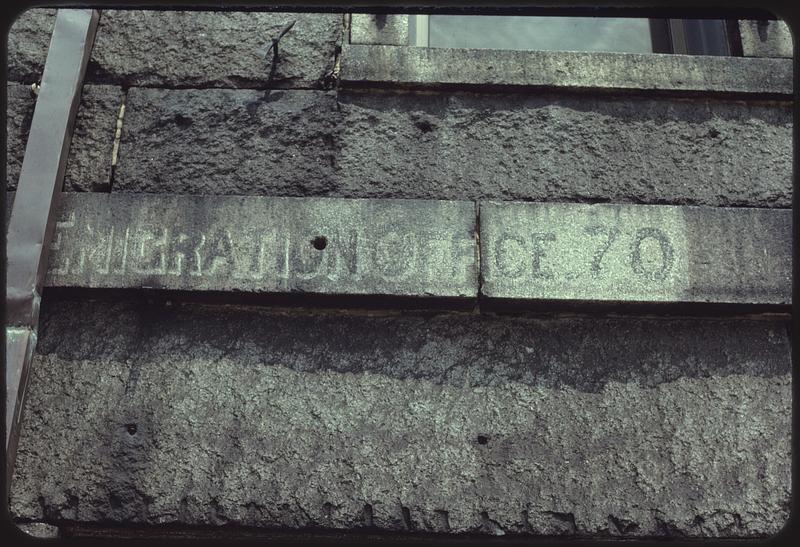

Custom House Block

Custom House Block building, photographed in 1975.

The Immigration Station and Detention Center on Long Wharf was adjacent to the Custom House Block building, one of the iconic historic buildings that still stands there. Custom House Block was built by 1849, and rented to the government to serve as Appraisers Stores shortly after. Appraisers stores were spaces the government would use to hold merchandise for inspection before it was sent onward. The building originally had space for 14 stores, but within a few years, the five on the eastern end were demolished and replaced with freight sheds. It was the second floor of this end of the building that served as the Immigration Station and Detention Center in Boston until 1920.

Detention on Long Wharf

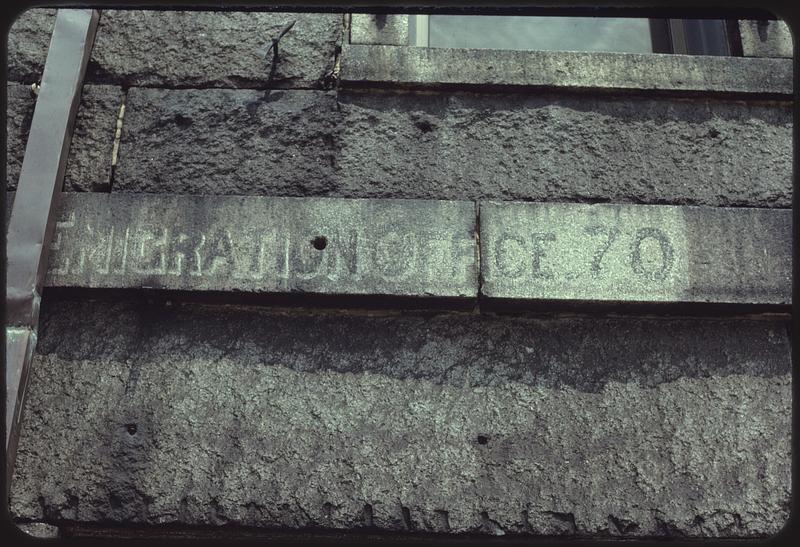

The “Emigration Office” sign, photographed in 1975.

By the twentieth century, the Immigration Station and Detention Center on Long Wharf was widely considered unsafe. Its building, along with the other facilities on Long Wharf, was at constant risk of fire. Many folks were also detained because they had contagious illnesses and could not be let into American society—as determined by immigration officers. Historian Kelly Kilcrease says the station was likely too small for its purpose from the outset, and the next purpose-built immigration station was designed to hold over 500 people. In 1907, Congress designated $250,000 for a new fireproof facility to be built on new land. Local authorities rejected Castle Island and Governors Island as new locations, and in 1911, a site in East Boston was chosen. This site at the end of Long Wharf was closed when the new location opened in 1920.

The easterly end of Custom House Block in 1903.

Stories from the Boston Daily Globe

The Boston Daily Globe newspaper reported on remarkable happenings at the Immigration Station and Detention Center, often in its “Water Front Items” column alongside news of ship arrivals and departures and new items for sale. These are just a handful of stories from 1907-1909. These cases highlight Long Wharf as a borderland and place of transition—a direct pathway into Boston, but still on the periphery of the city itself.

Mariam Zartarian – January 15, 1907

Mariam Zartarian arrived at age 15 with her mother and brother in April 1905 to meet her father, who was a naturalized citizen. Her mother and brother were released to her father, but Mariam was held because she was ill with trachoma, an eye infection. By June of that year, she was deemed out of danger and no longer contagious, but she was still denied entry. Inspectors disagreed over whether her father’s naturalized status granted her citizenship, and her case was appealed all the way to the United States Supreme Court. All the while, Mariam was held for twenty months at the Immigration Station and Detention Center on Long Wharf. She was finally released into her parents’ custody in early 1907.

Varter Bedros Eayan – January 5, 1908

Varter Bedros Eayan arrived on a White Star Line steamship on Friday, January 3, 1908, to marry her lover who was already in Boston. Her brother, who lived in Philadelphia, objected to the marriage and a Board of Special Inquiry was convened to decide her fate. She was held overnight on Long Wharf while the Board deliberated, until the next morning:

“I love you Khorem.” sobbed the girl. “I shall go to Philadelphia for a month and then I will come back to you and no man will ever separate us again.” Crying as though her heart would break the girl was led away by her brother, while her lover gazed after her with tears streaming down his face.

Chan I Ying – January 9, 1909

Chan I Ying was held at the Immigration Station and Detention Center on Long Wharf when she was arrested in Boston after fleeing from her abusive husband in New York. She and her landlady were accused of stealing silk from the husband, but her lawyer, Thomas J. Barry, saw no reason for her to be deported and fought for his client to stay in Boston.

Marie Manbrine – November 8, 1909

Marie Manbrine, long known for playing the hurdy-gurdy in the streets of downtown Boston, was detained on her return voyage from Italy where she had gone to be married. Her husband’s luggage had a false bottom filled with smuggled jewelry. Marie had given birth on the voyage, but the baby died the day they arrived, and Marie was first taken to a hospital in the city. She was then moved to the Immigration Station and Detention Center on Long Wharf to be questioned about the smuggling. Though both she and her husband claimed innocence, the Globe writes confidently that they would likely be deported.

Towards Beacon Hill

Towards Beacon Hill