This essay was written as a student project for HIST 7250: Practicum on the Place-Based Museum at Northeastern University in Fall 2024.

Boston’s Financial District has had to make many transitions as the financial landscape of the United States has changed. Today’s Financial District used to be the waterfront, and with good reason. For many years, Boston’s business sector was dominated by trade and other businesses that relied on the port. However, as the importance of trade to the Boston economy lessened, businesses like banks and insurance companies began to build skyscrapers and set up shop in the area. As the 1870s began and Boston continued to grow by filling in land, the Financial District faced a crisis.

In the late 19th century, the existing neighborhood and infrastructure changed forever, when it was essentially destroyed in a devastating fire. While the fire had a relatively low human cost, the neighborhood had to be reimagined to not only be more resistant to fire, but also to revitalize the businesses that called it home.

The Fire

While Boston underwent many gradual changes in the 19th century, the Great Fire of 1872 created devastating destruction that would change the city, and especially the Financial District, forever.

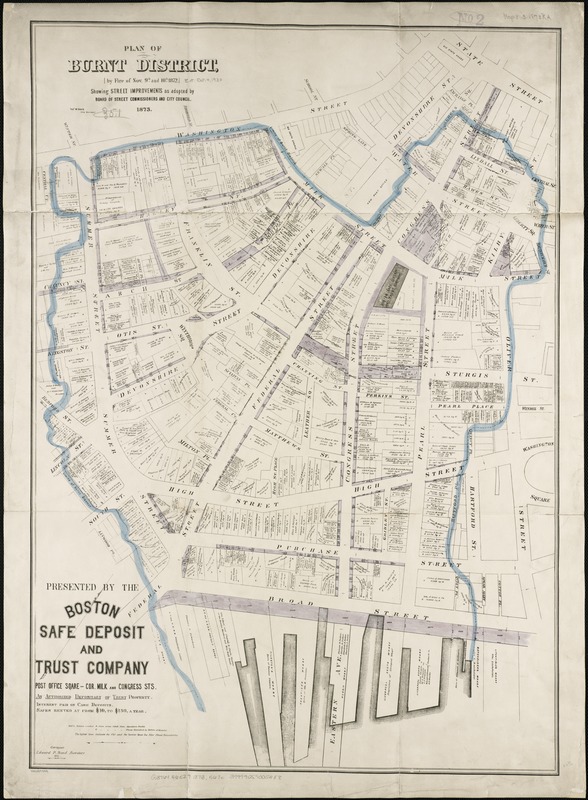

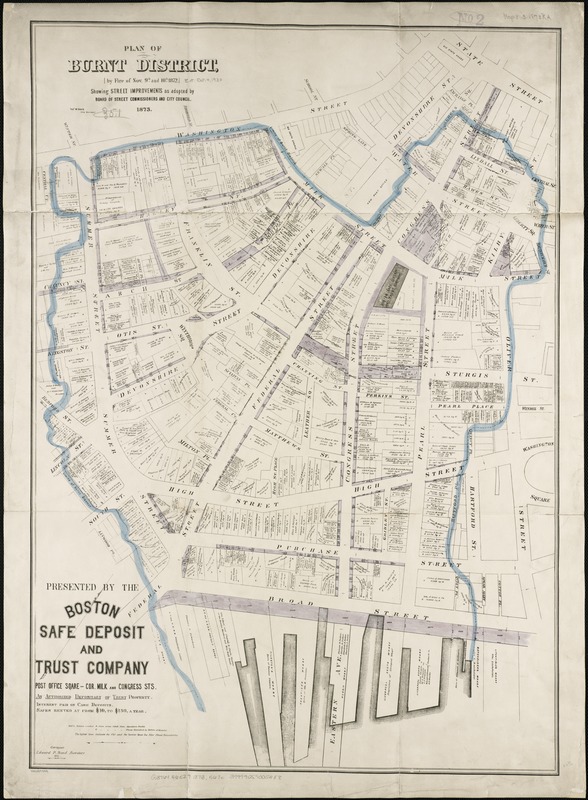

The fire began on November 9, in the basement of a warehouse on Summer Street. It spread so quickly and intensely that it burned all wood buildings, and even melted some metal buildings in the area, totally 65 acres of damaged space. The image below shows a 1872 map of the damaged area.

The fire set records for the amount of monetary damages it caused, but for a fire this large and hot, relatively few lives were lost, compared to a year earlier in Chicago, when a fire caused over 300 deaths. Counts differ on how many died in the fire, but estimates are from 11 to 300, with about a quarter being firefighters.

History and the Fire

The history contained in the Financial District also played a part in the firefighting process. While many buildings were lost in the fire, firefighters stopped the fire around the intersection of Washington and Milk Streets. This is important because much of the effort of the firefighters was devoted around this intersection, because of the proximity of the Old South Meeting House. Saving the Meeting House was a priority of firefighters, because of its historical significance. The importance of Revolutionary history to Boston has existed since the late 19th century, and the preservation of these buildings through a devastating fire is exemplary of that importance.

The damage from the fire on Washington Street looking towards the Old South Meeting House.

While the Old South Meeting House was saved, other historical landmarks were lost. One such landmark was the original Trinity Church. Trinity Church was consecrated in 1735 on Summer Street in the Financial District. It was lost in the fire, with a shell of the building remaining in the wake, as seen in the image below. The congregation was then moved to Trinity Church that still stands in Copley Square. Also lost in the fire were two local newspapers headquarters, as well as seven banks. Today, at the previous site of the Church at Hawley and Summer Streets is retail shops, and a block from the Downtown Crossing T stop.

Trinity Church after the fire.

Rebuilding and Effects

An important reason why the fire was not as deadly as other large fires in urban centers was that there were very few residential buildings affected. Since the influx of businesses to Downtown Boston in the early 19th Century, most of the damage was done to warehouses and office buildings. The city of Boston began to plan once again for a district where many would work, with a commercial focus. Below is an image of the plans from 1873, less than a year after the fire.

While the fire had wiped out the neighborhood and caused millions in damage, the quick action of citizens to rebuild showed the motivation to get the financial center of the city up and running. The rebuilding efforts are illustrative of Boston’s resilience, especially within the business and economic center. The scale of damage allowed for an overhaul of the neighborhood. A committee of Bostonians formed to urge the city to make changes that would make streets wider and straighter, and therefore make the streets safer and fire harder to spread among buildings. The resulting changes were significant: seventeen streets were widened and four were extended. The city also implemented significant upgrades to its firefighting abilities, hoping to curb another fire.

The pace of these changes was remarkable. The current District is the result of a resilient city, that would not accept long term, widespread damage, or a repeat of the devastating fire. The importance of the district as a financial center, not a residential one, made it a unique place, did the intermingling of historic monuments. This colossal event was essential to the making of Boston’s Financial District, and exemplify the city’s innovation and resilience.

Towards Beacon Hill

Towards Beacon Hill